The making of Prisoners in Paradise is like a three stage rocket. The first phase began in May 1989 when singer Joey Tempest, guitarist Kee Marcello, bassist John Levén, keyboardist Mic Michaeli and drummer Ian Haugland set up base in California to write, rehearse and record an album on the other side of the Atlantic for the first time. The change of scenery wasn't the only new thing. In a warehouse in San Francisco, the material would for the first time be put together by a collective. Gone were the days when pretty much all of the songs were written by Joey Tempest.

"We had a discussion and decided that everyone else in the band would be more involved in the songwriting," says Joey. "They had started to become more interested in it. They had gotten better and put more time into writing. Mic has always been very musical and had ideas, but here he started to get down to action with his material. Of course, Kee was also a songwriter and Levén started to come up with ideas. I welcomed it, I thought it was fantastic. We knew each other so well that it was easy to put the material together collectively."

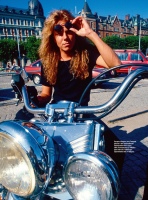

For the most part, the band was living together. Each member had an apartment in a rental complex in San Francisco. Every morning they took the elevator down to the garage, hopped in two Chrysler LeBaron cars and went to the rehearsal room.

"Earlier, Joey had sent demos to us and then we'd meet up to rehearse them," says John Levén. "Now that we were living together and going to the rehearsal room every day with the mindset of writing songs, it was a different vibe. It was different to start from scratch, all together. Maybe that's why it became a little more guitar oriented and more relaxed. Out of This World had been more of an attempt to follow up The Final Countdown. Now we thought, 'Fuck it, let it loose.' Not that the previous albums were bad, but we thought we should riff it up a little more on the next album."

"For the first time I started to use 'drop-D' tuning in EUROPE," says Kee Marcello. "I had previously used this guitar tuning when I played on Mikael Rickfors' soul album Rickfors in 1986. Back then I did it because I liked to capture the chords in a different way, but now I did it to make the riffs sound fatter."

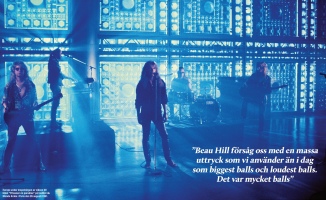

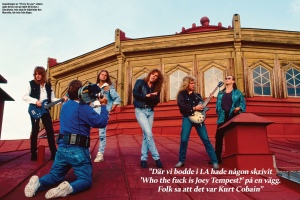

In England, the recurring hard rock festival Monsters Of Rock had to be canceled after the previous year's tragic accident when two spectators lost their lives in the turmoil that arose in the quagmire in front of the stage. In its place, on August 19 - the same day that Joey Tempest turned 26 - a one-day event was held at the National Bowl Amphitheater in Milton Keynes. EUROPE had been given the spot just below headliners Bon Jovi and made a detour from the rehearsals in San Francisco. The turnout was huge - 60,000 people - when EUROPE took the stage led by a straight-haired singer. The fact that the poodle hair was now history was symbolic. EUROPE were set to show that they had more than ballads and grandiose synth fanfares to offer. Daringly, they played four songs that were so new that no one had heard them - "Yesterday's News", "Seventh Sign", "Little Bit of Lovin'" and "Wild Child". The procedure was sassy. So was the material. The reaction did not take long. The important hard rock magazine Kerrang was so taken aback that they considered EUROPE to be louder than Motörhead. On the plane back to San Francisco, the five Swedes could be happy with their surprise attack. They had earned valuable hard rock credibility for their upcoming album.

Having tried out the new material in Milton Keynes, it was time for Los Angeles. On September 17, the band booked the legendary venue Whiskey a Go Go on the Sunset Strip. Another new song, "Bad Blood", had been added to the setlist. However, they would not perform as EUROPE.

"At that point we could have probably sold out an arena like Irvine Meadows, but we wanted to do a secret gig," says Kee. "It was the in thing to do and it was a perfect opportunity to see how the new songs would go down. We called ourselves Le Baron Boys, because Chrysler sponsored us with their cheaper LeBaron cars during the making of the album."